| |

|

| |

| |

|

You might think that

painting a violin or a string instrument generally

concerns only aesthetics and conservation as well

as making it pleasant to touch and sight. All those

issues would be worked out by a good coat of "copal"

or a little more. It is so in most cases of wooden

handworks. On the other hand, if the artefact should

become, for instance, a valuable piece of furniture,

the cabinetmaker would keep busy to get nice color

effects and light reflections from the treated surfaces.

In case of a high quality violin making, the matter

gets a little more complicated because the artefact,

in addition to show the above mentioned features,

has to perform a much more difficult task: playing.

And it must do it very well.

In a string instrument, the vibrations originated

by the strings spread through the bridge across the

soundboard to the back through the sound post causing

a resonance within the sound box coming into the surroundings

through the typical f-shaped slots called "harmonic

holes". The technique and the kind of substances

used to paint the surfaces affect the way the wood

reacts to vibrations.

|

|

|

The

famous violins by Antonio Stradivari, legend has it,

hid their excellence just in the painting technique

but legends, you know, are destined to remain so.

Marco Cioni studied hard the books of the ancient masters

and experimented their painting techniques and preparation

of bases and pigments for years. His words reveal some

scepticism about secrets and legends. He declares:

"There is a lot of talk of Stradivari's paint and

secret but there are no secrets in violin making. The

result depends on the luthier's hands. It's only this,

along with the ability to comply with certain basic

parameters, that makes the difference".

Therefore a clear stance supported by Marco, as he points

out, by the fact that, if Stradivari had kept any secrets,

he would have certainly passed on two sons of his who

followed the art of violin making but who never reached

the ability of their illustrious father. Furthermore

it is known that in the early eighteenth century, in

Cremona, there was a workshop at least. All the luthiers

used to get there the same resins and pigments.

However, we can say that, besides a great experience

in dosages and application techniques, each artisan

eventually keeps his "secrets". |

|

|

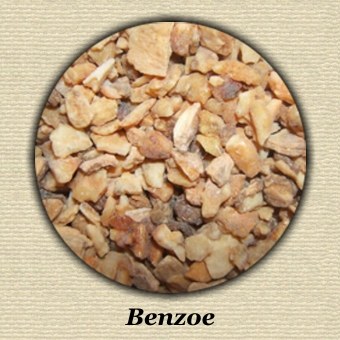

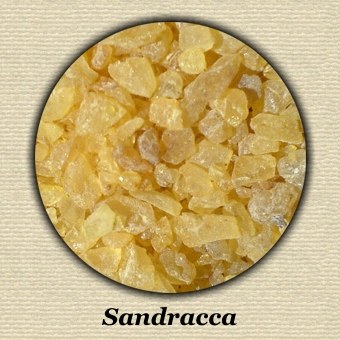

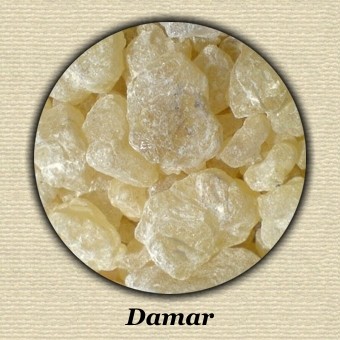

In violin making paints

mainly contain ethyl alcohol (spirits) in which particular

and precious natural resins are melted. They are also

called gum resins like Benzoe, Sandarac, Damar, Copal,

Mastic in Tears, together with some coloring agents,

such as the root of Turmeric, sandalwood and Caliatour.

Alternatively, some boiled linseed oil is used to

prepare the paint based on fossilized Amber, a substance

a little more difficult to treat than the gum resins.

However, just with the fossilized Amber from mine

or from the Baltic sea shore, Marco achieved his best

results. "It was no easy to find out the procedure

to get the paint of the ancient violin makers",

he says.

In fact the Amber, also called "succino"

or "succinite" because it contains succinic

acid, is the result of Copal fossilization, a resin

emitted by some conifers, which solidifies in the

course of 3 - 4 million years thus becoming very hard.

It can vary in color, from yellow to red, brown or

green and can be dissolved in chloroform, benzene

or other similar solvents. The latter ones, certainly

not available at the time of the ancient violin makers.

Then, how did they manage to use it ?

Marco says: "After a period of research I found

out that the only way to make the Amber malleable

they had at that time was to heat it to about 350

C° in iron containers called "flasks".

This process frees the succinic acid from inside and

the substance becomes doughy and soft".

However, before melting the Amber, it is necessary

to thoroughly wash it with sodium hydroxide, commonly

known as caustic soda, in order to remove impurities

from the surface. Then, meanwhile you proceed with

the Amber, it is also necessary to heat the boiled

linseed oil up to the same temperature of the resin.

Mixing the two ingredients, when the temperature begins

to drop, some turpentine must be added. This is when

you can choose to maintain the natural color of the

preparation or to get a more brownish paint. To do

so you need to treat turpentine in advance with the

dye it only accepts, that is, the "bitumen of

Judea".

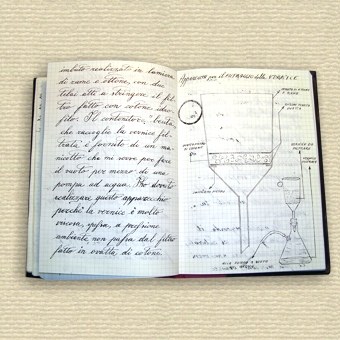

Once cooled the mixture is not ready for use yet because

it shows some suspended impurities to be removed.

Some of these, being heavier, may settle in a short

time but the others, mainly slag, keep suspended so

that filtering is needed. In this regard let's go

back to Marco's notebook clicking the image on the

side.

"The first time I performed the procedure at

home", says Marco, "the smell of acid didn't

vanish for a week! Since I discovered the Amber, let’s

say, I mostly use the oil-base paint for my instruments

although, compared to alcohol-base paints, it needs

much longer time to dry. But the result is excellent

for both aesthetics and sound".

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Finally look at the pictures below showing two painted

violins. One (on the left) with alcohol-base paint and

the other (on the right) with oil-base paint. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|